Silicon carbide chips: Teaming up to produce a key technology of the future

How cross-border knowledge exchange will enable a big boost for electromobility

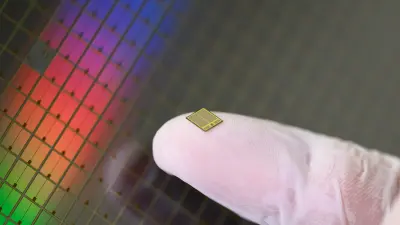

Our modern world would be unthinkable without semiconductors. They’re already in everything from smartphones to cars, and now the global ramp-up of electromobility is sending demand skyrocketing — particularly for semiconductors based on the innovative material silicon carbide.

The future is silicon carbide

It’s no exaggeration to say that semiconductors power the modern world. From consumer electronics and vehicles to industrial machinery and energy infrastructures, there is practically no domain left that doesn’t heavily rely on them. The numbers certainly back this up: in 2023, more than a trillion of them were produced and sold. Particularly in demand are cutting-edge power semiconductors based on silicon carbide, often abbreviated SiC. This innovative material is especially important for the promise it holds in bringing us a step closer to fully electrified mobility, since its increased power density enables greater range and more efficient recharging for electric vehicles. Ramping up capacities to meet demand is shaping up to be a challenge, however, since SiC chips can only be produced in specialized wafer fabs.

One of these specialized facilities is in Reutlingen, Germany. Here, Bosch has been producing semiconductors continuously for over 50 years. It’s currently the company’s sole production site for silicon carbide chips, but it will soon be joined by another: with the acquisition of an existing wafer fab in Roseville, California, Bosch plans to significantly expand its production capacities of this key technology. In order to convert the new fab to state-of-the-art silicon carbide chip manufacturing, the company plans to invest some 1.5 billion U.S. dollars, though the full scope of the planned investment will be heavily dependent on state and federal funding opportunities. After the upgrade, Roseville will make SiC chips on 200mm wafers, which are considered the gold standard for their superior cost-effectiveness and higher production volumes. The first silicon carbide chips are scheduled to be produced in 2026.

A transatlantic training scheme

Before that, however, a lot has to happen. The Roseville fab previously produced standard silicon-based application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs); the facilities now need to be overhauled to handle the much more demanding silicon carbide. The good news: existing clean room facilities and a specialist workforce in Roseville will allow Bosch to relatively quickly switch over to manufacturing SiC. It’s not entirely straightforward, however — silicon carbide requires replacing most of the site’s equipment and machinery. And then there’s the 250 Roseville-based associates that Bosch gained in the acquisition, who have to be retrained in new manufacturing and testing processes. That’s no easy feat, as expertise in these cutting-edge methods is still a somewhat rare commodity. Of course, one of the few places it does exist is in Bosch’s plant in Reutlingen — half a world away.

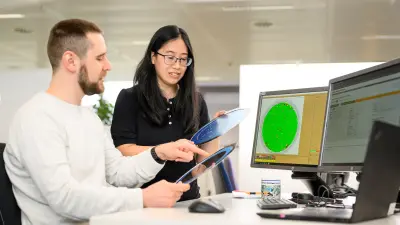

To help facilitate the transfer of knowledge gained in its existing SiC wafer production, Bosch is employing a cross-border training scheme. It works on the buddy principle: an engineer from the Roseville site is brought over to Reutlingen and paired up with an experienced local engineer whom they shadow for several weeks. “This is a way of leveraging the greatest asset we acquired in Roseville — the 250-strong workforce, all of whom are established semiconductor experts,” explains Dirk Kress, who heads Bosch’s global semiconductor operations. “Thanks to this training program, we’re strengthening our global manufacturing network, the success of which depends on strong interpersonal relationships and knowledge sharing. Ultimately, this will help Bosch cement its position as a leading SiC manufacturer — and give a boost to electromobility on a fundamental level.”

A low-tech method for learning high-tech processes

In total, about 60 Roseville associates are taking part in the program. Among them is 26-year-old process engineer Allison Suba. Allison is spending three months on site in Reutlingen working alongside 30-year-old process engineer Tobias Huschitt, who already has two years of silicon carbide chip production under his belt. He’s helping her get comfortable with the new processes she’ll be responsible for when production resumes in Roseville — which include, among other things, mounting the silicon carbide wafers on frames, processing them in the dicing machine, and analyzing the resulting chips for faults.

“At the end of her time here, she should be able to do these things in her sleep,” Tobias says with a smile. Allison, for her part, is soaking it all up like a sponge. Apart from the new machines and processes, she was surprised to find that her daily routines in Reutlingen are not so different from those back in Roseville. With one exception — lunch. “Germans take lunchtime very seriously — everyone stops what they’re doing and goes together to the cafeteria. That’s a custom I wouldn’t mind bringing back to Roseville with me,” she says enthusiastically.

Of course, the program is not without its challenges too. Allison and Tobias agree that even though three months sounds like a long time, it’s actually a tight timeframe to bring someone up to speed on technology as complex and exacting as this. “A year would be better,” Tobias remarks, “but we don’t have that, so we have to make every minute count.” Neither have any doubts about the basic validity of the training model, however. Both wholeheartedly agree that despite the cutting-edge nature of the processes, the best way of learning the ropes is by employing the oldest technique in the book: working side-by-side with an expert partner. “It’s great that a global high-tech giant like Bosch recognizes the value of face-to-face knowledge transfer. I’m benefiting directly from Tobias’s experience — that’s a resource you can’t get anywhere else,” Allison says. But does that mean she’ll be ready when the production lines are switched on in Roseville? Her response comes without hesitation: “Oh, without a doubt! Tobias is a great teacher — every day I feel a little more confident in my abilities.”

A semiconductor pioneer with a foot in the past and the future

This seamless integration of old and new could be a metaphor for Bosch’s overall involvement in semiconductor production. Bosch is widely regarded as a pioneer in this field; the company started producing power diodes as long ago as 1958. At Bosch’s Reutlingen plant, application-specific integrated circuits have been manufactured continuously since 1970. Since the end of 2021, silicon carbide chips have been produced here as well — initially on 150mm wafers, though starting in 2026, the first 200mm wafers will roll off the line here too. This essential piece of technology will thus soon be produced at both Bosch’s oldest semiconductor location as well as its newest — thanks in large part to this training program. If all goes according to plan, the program will result in a faster ramp-up in Roseville, fewer production errors, as well as a big boost to Bosch’s ability to supply this key component for electrified mobility. But there’s an important side benefit, too: a string of new cross-border friendships, like the one Allison and Tobias are forging over three intense months of mounting, dicing, analyzing, and of course lunching together.