Three decades of electronic stability program

ESP® — thank heaven for electronics

By 2025 more than 22,000 lives have been saved and almost three-quarters of a million traffic accidents involving personal injury have been averted in the EU and UK alone. Worldwide, Bosch itself had already supplied more than 350 million such anti-skid systems by then. It is one of Bosch’s biggest innovation stories, and is a prime example of the “Invented for life” ethos. In no time at all, the electronic stability program earned itself the nickname “electronic guardian angel” and became the subject of stories and legends. These tales of elk tests and other maneuvers are worth revisiting.

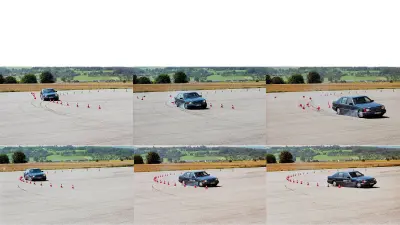

The setting of our first story is the very same airfield in Renningen where Bosch would build its research campus many years later. It is the summer of 1994, and the air over the faded asphalt runway, which even then was a test site for the company’s engineers, is shimmering in the July heat. Our vehicle accelerates to 100 kilometers per hour before making a sharp left at full speed. What sounds like an accident in the making is, in reality, the blueprint for a test. As a control experiment, we switch off the anti-skid system. Anton van Zanten, the head of the ESP® development project at Bosch, remains cool as a cucumber. The car picks up speed, then Zanten abruptly turns the wheel. The tires squeal; the car swerves. When it finally comes to a stop, it is obscured by smoke and the stench of burning rubber. Almost frantically, Zanten’s passenger tries to retrieve something to write with, as all his pens have been flung to the far corners of the vehicle. “With the anti-skid system on, you’ll be able to take notes as we round the corner,” van Zanten says with a wink, while he gently guides the car back to its starting position. And he’s right: we repeat the process with ESP® turned on, and the outcome — at least technically speaking — is far less dramatic. We speed back up to 100 kilometers per hour before taking a sharp left. But this time, there is no sudden swerving, no smoking tires. The vehicle stays on track, the wheels perfectly in line with the steering-wheel angle, as if we had an electronic guardian angel on board.

The yaw-rate sensor — the heart of ESP®

Yet before this guardian angel can go into production, there are still many obstacles to overcome, and consequently also many tales worth telling. For example, there is the story of the project unit where Bosch and Daimler, its pilot customer, join forces to develop ESP® for the Mercedes S-Class. That alone shortens the development time by 25 percent, or one full year. Getting the yaw-rate sensor ready for large-scale production and making it cost-effective is no easy feat. This sensor is the heart of ESP®, but the principles behind it lie in the world of aerospace engineering. In a rocket, it only has to last one flight. In a car, however, it has to keep working for ten years. Still, the engineers manage to get it on the road. Later, they turn it into Bosch’s first micromechanical sensor, the kind that will one day rotate smartphone screens in the right direction. But that’s another story.

Like a rail through the ice

Meanwhile, the first images of ESP® in action are recorded using a helicopter-mounted camera — as if James Bond rather than a guardian angel were playing the starring role. We have left the July heat behind us. It is March 1995 in the northern Swedish town of Arjeplog, where the anti-skid system is being put through its paces on a frozen lake in the biting cold. A helicopter appears out of the whitewashed sky, stirring up snow as it lands on the thick, almost impenetrable ice. Windblown figures waiting by a modern-day automotive wagon train approach the flying machine. They are not the ragtag remnants of a failed arctic expedition, but rather a film team waiting for the chopper to take them up to get aerial footage of the ESP® system in action. With barely a word, the cameraman climbs into the waiting whirlybird and straps himself and his equipment in. The door has to remain open, even during the flight. High in the polar air, he films two vehicles: a red one and a green one in the snow, one with and one without ESP®, one swerving and one forging its path straight ahead, as if being pulled on a rail through the ice.

The “elk test” and its consequenses

Yet it will still be another two and a half years before ESP® receives the unexpected boost it needs to be a commercial success. And once again, Sweden factors into the picture. It is October 1997, and suddenly “elk test” is on everyone’s lips. At an airfield somewhere in the Swedish forests, this tried-and-tested evasive maneuver test has managed to flip a Mercedes A-Class, shortly before the car is due to be launched. The accident has momentous consequences, since Bosch soon receives an inquiry as to whether its ESP® could help make the A-Class flip-proof. The board of management, led by Hermann Scholl, recognizes the opportunity and embarks on a race against time. Everyone knows the elk test, everyone knows what is at stake — and everyone is on board. Engineers from Schwieberdingen sacrifice their weekends to deliver the latest software updates.

Daimler and Bosch breathe new life back into their joint project unit. “Both sides are in it with such dedication that it no longer matters who is the client and who is the supplier,” the task force leader Harald Schweren says.

The situation at the plants, however, is tricky. The task at hand following the elk test is to make ESP standard equipment in the A-Class, and so far greater volumes are needed than before. Associates in Blaichach find themselves confronted with the task of ramping up ESP® hydraulic modulator production faster and in much greater steps than planned. Nuremberg even has to set up a second production line for yaw-rate sensors in less than three months. That means investing an additional 20 million German marks, installing machinery, and getting it running. Sometime between Christmas and New Year, the special-purpose machinery team completes its work on the production line in Nuremberg. The circumstances are so exceptional that the plant management and the works council reach a separate works agreement in record time. After just a few days of negotiations, they agree on 21 shifts a week, including Sundays. “We’re very flexible when it comes to products with a promising future,” says Helmut Sprethuber, the works council chairman.

It is this flexibility and rapid reaction that secure the future of ESP®. Rapid reaction is what gives the electronic guardian angel the technological edge, allowing it to brake individual wheels within a split second, to keep cars from breaking out of a curve. But following the elk test, an entire team reacts rapidly and with presence of mind, from the board of management seizing the opportunity to turn a negative into a positive, down to the engineers and associates on the assembly line. All of them demonstrate outstanding dedication and commitment. It is their hard work that makes it possible for the A-Class to safely take to the roads in early 1998 – equipped with an anti-skid system that is now able to prevent it from flipping over. Its success makes Mercedes’ competitors want to keep up, and so ESP® rapidly becomes a feature of other mid-sized cars. In Europe, ESP® has been mandatory in all vehicle classes since 2014. The benefits of electronics have now become a standard feature.

“Both sides are in it with such dedication that it no longer matters who is the client and who is the supplier.”

Author: Ludger Meyer