Eco-friendly mobility needs more competition

2019-07-10

A plea for more open-mindedness on the path to CO₂-neutral road traffic

by Dr. Volkmar Denner

In a number of languages, it’s only a short step from “engineer” to “ingenious” and the idea of creativity inspired by curiosity. And what can set such creativity free? A dispassionate, open-minded assessment of what is possible. Driving around without consuming energy will remain in the realm of fantasy, like the idea of a perpetual motion machine. Driving around without emitting CO₂, on the other hand, is within the realms of possibility. For it to happen, however, the various innovative possibilities have to compete with each other to find the automotive powertrain that offers the ultimate green form of road traffic. Only technological open-mindedness will stimulate the ingenuity needed to solve problems, no matter how complex.

“Driving around without consuming energy will remain in the realm of fantasy. But driving around without emitting CO₂ is within the realms of possibility.”

For climate-neutral products

A technology company that takes climate action seriously should be guided by a dispassionate, open-minded assessment of what is possible. Bosch is already taking a huge stride forward by making its locations worldwide CO₂ neutral by 2020. But in the end, the issue isn’t just one of locations. Products themselves have to be made as carbon neutral as possible. For us as the world’s biggest automotive supplier, this means entering the contest to find the most carbon-neutral form of road transport.

75 percent

of new cars will still have combustion engines, in 2030. That’s why these engines have to be part of the solution.

What the automotive industry can do

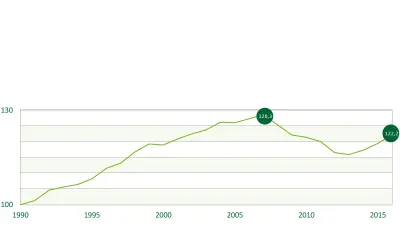

Such a venture starts with a sobering realization. The CO₂ emissions of Europe’s road traffic have risen 22 percent since 1990. They reached their peak in 2007. And while emissions levels have fallen since 2007, That said, complying with the Paris climate agreement would mean making European road traffic carbon neutral by 2050.

What can the automotive industry do? It can come up with alternatives, and market them. Such alternatives include electromobility, from batteries to fuel cells. However, technological open-mindedness also means seeing modern combustion engines as part of the solution. Indeed, they have to be part of the solution, since they will still be powering three-quarters of all new cars worldwide in 2030, with only a quarter driving purely electrically. All the same, diesel and gasoline engines can be extensively hybridized, and their CO₂ emissions reduced from their current level of over 100 to 20 grams per kilometer.

From well to wheel

But this only applies to the energy consumed from tank to wheel. It is at least as important to consider what happens between well and tank. Optimizing engines will not be enough, therefore. One possible solution is renewable synthetic fuels. A combustion engine that runs on such fuels can be climate neutral. Such a saving should be included in the way fleet values are calculated under the EU’s CO₂ regulations. Let’s make no bones about it: electric cars are only carbon neutral if their electricity comes from renewable sources. This widens the scope of our considerations. In road traffic, climate action is not just something that applies to actual driving on the road, but from well to wheel.

“Open-mindedness could be encouraged by carbon pricing – in the form of a tax on greenhouse-gas emissions, for example.”

Avoiding rebound effects

In the end, it is about laying all our cards on the table, and presenting all the facts about the entire energy chain, as well as about real consumption on the road, and not just in a standard test cycle. When clarity like this meets ambitious targets, the result is a race to innovate, instead of political bias toward a certain technology, whether combustion engine or electric motor. Clarity about targets allows us to be open-minded about the technological solutions available, and such open-mindedness fosters competition to find the best technologies.

Such open-mindedness could well be encouraged by carbon pricing – in the form of a tax on greenhouse-gas emissions, for example. A technology-neutral CO₂ surcharge could at least prevent the rebound effects caused by lopsided subsidies. Deliberately promoting electric cars, for example, could cause demand for less sought-after vehicles to collapse. However, the law of supply and demand would mean their prices would drop until demand picked up again. As we see, it can be counterproductive for policymakers to act against the market.

Building a hydrogen economy

That said, the economics of climate action is not a simple matter. As is well known, CO₂ avoidance costs vary widely from industry to industry, and are significantly lower in power generation than in transportation. In other words, CO₂ pricing alone will not bring about climate neutrality in all sectors of the economy. It needs to be backed up by other measures. Revenue from a CO₂ tax could conceivably also be reinvested in transforming transportation.

In keeping with an open-minded approach to technology, this would allow at least two approaches to powertrain modernization to coexist: first, that of improving the recharging infrastructure for electromobility and, second, that of establishing a European hydrogen economy. This would not be promoting a certain technology. Instead, it could create the infrastructural conditions for competition between technologies.

“At the latest when air and sea transport have to become carbon neutral, there will be no avoiding the need for new fuels.”

Closing the gap with synthetic fuels

At the present rate of progress, road traffic electrification will not be enough to meet the 2030 climate targets. This was the conclusion recently drawn for Germany by the national platform for the future of mobility. Indeed, the German Transport Ministry has identified a “climate gap” for the coming decade, which will have to be filled by, among other things, roughly three million tons of alternative fuels. We therefore need both electromobility and renewable synthetic fuels. At the latest when air and sea transport have to become carbon neutral, there will be no avoiding the need for new fuels. This is what technological open-mindedness is about: doing all we can to bring new energy to climate action.

First published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on 07/10/19.