Jumping to conclusions

2020-05-07

Electromobility and renewable synthetic fuels — climate action needs both. A plea for more realism in the move to alternative mobility.

by Dr. Volkmar Denner

Electricity is a highly charged subject. This is as true for physics as it is for the debate about alternative mobility. It’s good that electromobility is coming, but also good that a logical inconsistency is slowly causing people to reconsider. It’s now becoming common knowledge that electric cars are only climate neutral if the electricity they drive on is generated from renewables.

But it’s another misunderstanding that we are having to fight. It is based on the assumption that diesel- and gasoline-powered cars can never be climate neutral. But in fact they can, if they drive on renewable synthetic fuels (RSF) — fuels made exclusively with energy from renewable sources.

Let’s not think like centralized planners!

And this is where another fallacy crops up: this time in the shape of the argument that there isn’t enough renewable energy to make all the synthetic fuels needed for road transport, let alone sea and air transport. An inflexible attitude, almost reminiscent of centralized planning. It ignores the first rule of market economics, where rising demand — in this case for synthetic fuels — leads to rising supply. The example of RSF illustrates how lacking in openness and constructive attitudes the debate about alternative mobility is. It’s not so much a debate as a series of hasty conclusions.

“The example of RSF illustrates how lacking in openness and constructive attitudes the debate about alternative mobility is.”

New mobility means new energy

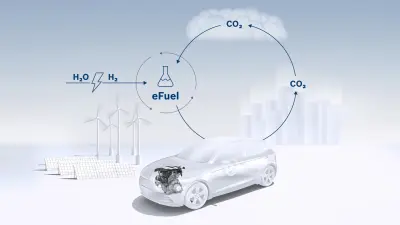

But what can we do to inject some realism into the debate? Our starting point should be the clear insight that the moves to alternative mobility and alternative energy are indivisible, and have to be thought of in these terms much more than before. After all, neither synthetic fuels nor electromobility will stop global warming unless they are based on green electricity. In simple terms, synthetic fuels are made by combining carbon dioxide and hydrogen. While the CO₂ is ideally taken from the ambient air, thus turning a greenhouse gas directly into a fuel, extracting H₂ requires a greater effort. This is because the climate-neutral extraction of hydrogen from water requires renewable electricity. And this, unfortunately, is where our debate gets entangled in fallacies once more...

Electric cars and RSF are comparably efficient

For one thing, it is often argued that a combustion engine powered by RSF consumes nearly five times more electricity than a comparable electric motor. In fact, for efficient combustion engines, a factor of three is a more realistic assumption. But then, people will argue, electric cars are much more efficient. That is true — as long as the renewable electricity is generated and used in the same country of origin. But what if the electricity comes from other parts of the world, where there is more wind and sun? Such electricity cannot be transported via power lines, but must be chemically converted, then converted back into electricity. At the end of such a chain, electric vehicles and RSF offer comparable levels of efficiency. As we can see, it would be helpful if the debate about alternative mobility were to stick to the facts more.

1.20 euro per liter

is what the net cost of RSF could be by 2030. By 2050, the cost could even drop to below one euro.

How the cost of RSF will fall

But how realistic is it to expect that we will be able to fill up with RSF at an acceptable cost one day? Here, too, we should not underestimate the power of market forces. It is of course true that synthetic fuels are still expensive. But the greater the production capacity, the lower the cost. By 2030, it will be possible to produce RSF at a liter cost of between 1.20 and 1.40 euros, net of tax, and by 2050 the cost could drop below one euro. That may still be more than we now pay for fossil fuels. But this cost advantage will soon shrink if a value is placed on renewable fuels’ environmental advantage.

Oil companies need an incentive

The 64,000 dollar question, of course, is how to put a cost on combating climate change. While carbon pricing is an important step, it can only be a first one. In the case of RSF, CO₂ standards for new vehicles offer a faster result. This would allow renewable synthetic fuels to be offset against the targets for fleet consumption. Just like a quota for the admixture of such fuels, this would be an incentive for oil companies to go into mass production of RSF. So why are European policymakers dithering? Because the lines between two different targets — one for automakers, one for fuel producers — might become blurred? If not shortsighted, such reasoning is at all events illogical. Even now, electric cars are considered in fleet consumption as though they were powered completely by green electricity. It is thus only fair to extend this cross-sectoral approach to include RSF. But above all, it is something that should have been done long ago. At the currently foreseeable levels of electromobility, Europe will come nowhere near its climate goals by 2030. Carbon-neutral fuels could help significantly close this climate gap.

Climate change won’t wait

These arguments apply all the more in that RSF can have an immediate impact on legacy vehicles. Half of all the vehicles that will be driving on our roads in 2030 have already been sold, and most of them have gasoline or diesel engines. These cars will also have to reduce their carbon footprint, and RSF will allow them to do so.

In other words, we have to be more open in our approach to alternative mobility — for the sake of our common future. Policymakers need to create the necessary framework conditions. Only if they do will renewable synthetic fuels be available in any appreciable quantity at our filling stations before the decade is out. We cannot afford to wait. Climate change certainly won’t.

First published in the “Tagesspiegel Background Mobilität” on 05/07/2020