One century of Bosch sensors

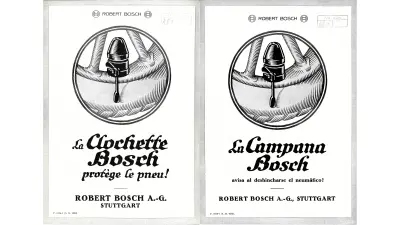

“The Bosch bell protects and warns motorists”

Bosch sensors are found wherever technology is in use. There are several of them in every other smartphone worldwide, on average 22 chips in every car. They help to prevent accidents, save resources, and protect the environment – and have been doing so for many years. Bosch brought out its first sensor a century ago. Named the Bosch bell, this solution warned motorists when they were losing tire pressure.

The road to becoming universal supplier

The brief success of the Bosch bell came in the period between 1910 and 1930, when Bosch was establishing itself as a universal supplier of automotive electronics. No longer a luxury toy for rich enthusiasts, cars were becoming an everyday means of transporting people and goods. They needed lights for the nighttime, windshield wipers for wet weather, and a horn to warn other road users. And who still wants to crank up a car when Bosch was able to offer an electric starter? Bosch committed to this business model and enjoyed great success.

Solution to the tire shortage

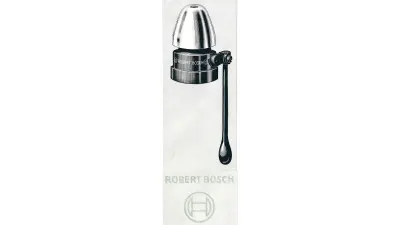

The Bosch bell

What was the need for the bell and what made it so successful? Quite simply, it was the right product at the right time: Car ownership increased significantly in the early 1920s, with the number of vehicles on the road tripling in Germany alone from 1910 to 1925. But tires were expensive, and that proved to be the catalyst for developing the bell. At the start of the 1920s, this boom in motorization coincided with a shortage of rubber, the basic ingredient of tires. Back then, liquid rubber was only harvested from wild trees in Brazil, which were suffering from a rampant fungal infestation. This caused the export of rubber — and with it tire production – to decline dramatically worldwide. Tires were extremely costly, and Bosch advertised the fact that a set of six Bosch bells was the cheaper option than replacing the rubber. “Paying for tires is the most painful part of driving a car,” wrote Bosch in one brochure.

How does the Bosch bell work?

A sudden loss of pressure often meant it was too late to save the tire. But the Bosch bell could help catch slow punctures, such as those caused by minor damage to the tire or a defective valve. Tires without enough air quickly became unusable. And with vehicles often running on extremely soft suspension, the like of which also featured on carriages, drivers could almost never detect a slight loss in pressure.

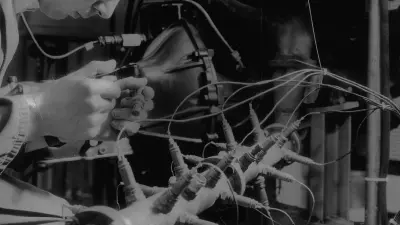

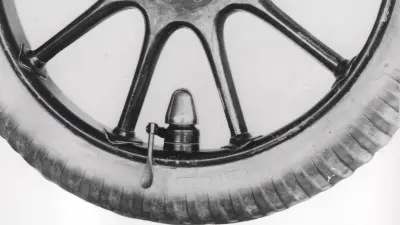

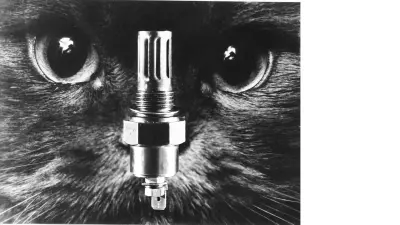

The Bosch bell was screwed on to each of the tire rims and consisted of a mechanical bell mechanism housed in an egg-shaped casing. The spoon-like toggle lever hung over the side of the tire toward the tire tread. If the tire lost air gradually, it would make the sidewall wider, pushing the lever away and triggering a loud ringing sound under the cup ... The motorist was warned and could refill the tire and look into why it was leaking air.

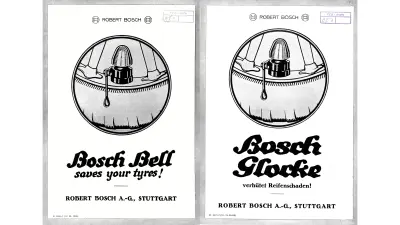

Worldwide marketing for the Bosch bell

Acting fast for short-lived success

Bosch started developing the bell in the summer of 1922, when tires began being in short supply. By spring 1923, it was ready to market. Once again, Bosch had proved its ability to quickly turn an idea into a finished product and manufacture it on a wide scale. Tire shortages were by no means a regional issue, so Bosch began marketing its bell system around the world that very same year.

Sales flourished, but the product’s success would be short-lived: Industrial cultivation of rubber trees in South-East Asia eased the tire shortage in the mid-1920s.

The Bosch bell’s brief period in the limelight had come to an end. The first sensor produced by Bosch was too expensive to protect a component that had once again become cheap to replace.

From mechanics to electronics

Apart from its function, this smart but relatively simple innovation has little to do with the sensors of today. The sensor technology of 1923 and that of the presence day are worlds apart. Increasingly sophisticated applications for sensors presented developers with new challenges and meant significantly longer development cycles. Bosch’s lambda sensor, for instance, which makes it possible to treat 90 percent of exhaust gases using a three-way catalytic converter, took seven years to develop. It also took much longer for acceleration sensors for airbags or wheel sensors for antilock braking systems (ABS) to reach series production than those first innovations. The greatest challenge for developers was achieving a high level of precision in high-frequency measurement. The lambda sensor has to be capable of measuring the exact exhaust gas composition in millisecond intervals, while the ABS has to monitor wheel slip at 40 to 50 fluctuations per second. The airbag sensor needs to tell the system to trigger the safety device within 40 milliseconds of a vehicle colliding with another object.

For the past century, sensor technology has been a recurring theme in Bosch’s history of innovation. Three decades ago, another milestone product entered mass production and laid the groundwork for today’s high-performance microelectronics in almost every application: the MEMS sensor used in microelectromechanical systems. Literally billions have been sold; Bosch has produced over 18 billion units since the start of large-scale production in 1995.

Tiny isn’t even the word for these micro-sensors. As one MEMS developer at Bosch once put it: “Don’t drop one on the carpet, you’ll never find it again.”

Author: Dietrich Kuhlgatz