One century of Bosch in India

“We need to take a different path”

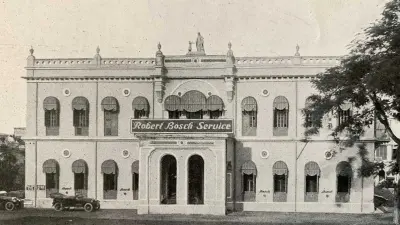

Bosch in India has a good reason to celebrate: The Company’s activities on the subcontinent began a century ago. The exact date is well known: on September 1, 1922, Bosch signed a contract with Illies & Co. Under this agreement, the long-established Hamburg-based trading company, with its extensive knowledge of local market conditions, was to sell Bosch products in India. From there, the path led via licensed production in the 1950s to Bosch's current regional companies in India.

The reasoning for starting business in India was simple: a century ago, the Indian subcontinent offered tremendous opportunities for Bosch. Automobiles needed an ignition system, and Bosch wanted to make its globally successful magneto ignition the standard in India as well.

Bosch also wanted to keep an eye on market developments in order to decide whether establishing a subsidiary, or even its own manufacturing plant, was worthwhile.

The move to India was part of a second wave of internationalization following the First World War. For Bosch, it was important to be present in all Asia Pacific countries that showed promising economic potential. The components made by Bosch had earned an excellent reputation worldwide, and this reputation promised good market prospects even in those countries in which the use of cars was still in its infancy. The company wanted to seize these opportunities itself, instead of leaving the Indian market to others to exploit.

Initially, therefore, magneto ignition systems, spark plugs, electric horns, headlights, and alternators were shipped from Stuttgart to the subcontinent – down the Neckar and Rhine rivers, via the North Sea ports, and around the Cape of Good Hope. Fierce competition from Britain, which was still a colonial power, made business difficult at first. Despite the good reputation of the Bosch brand and the high level of customer satisfaction, sales rose to just 150,000 reichsmarks by the late 1930s — less than 0.1 percent of the company’s total sales.

The main reason for the weak sales was that India’s roads were primarily populated by British and American cars, which came equipped with technology and parts from their countries of origin, and suppliers such as Lucas, Delco-Remy, and Auto-Lite. With the competition in a strong position to cover the need for spare parts, Bosch was left with whatever scraps remained.

The Second World War and the associated drop in exports to India exacerbated the problem. As the war wore on, Bosch’s sales offices ultimately closed entirely. And once the war was over, the company had a lot of obstacles to overcome before achieving its current market position in India.

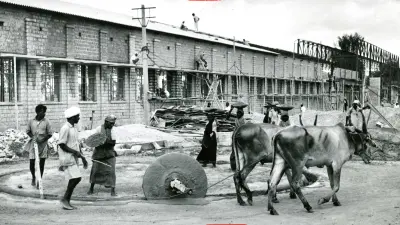

A first breakthrough came in 1951, in the shape of a partnership with the up-and-coming Indian company Ghaziabad Engineering Corporation and its subsidiary Motor Industries Co. Ltd. (Mico). Bosch granted Mico a license to produce spark plugs and diesel injection pumps. For Bosch, the alliance opened the door to the Indian market at a time when India, following the end of British colonial rule, was pursuing a highly restrictive licensing policy with respect to foreign companies. The partnership with Mico offered Bosch the prospect of becoming established on a lasting basis as a company manufacturing locally in India.

India’s first five-year plan helped prepare the ground. Adopted in 1950 by the democratic government under Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first prime minister, it called for the use of diesel engines to systematically irrigate fields. As a result, diesel injection technology for stationary engines became the first successful Bosch project in post-colonial India. In a market analysis written in 1953, Bosch experts ruled out any early end to the economic restrictions. However, they went on, Bosch could avoid future import risks by manufacturing in India — an approach that would open the door to stable and predictable business development. “We need to take a different path,” the authors wrote.

Thanks to an increasing level of motorization with diesel-fueled trucks, the automotive business operations of Bosch’s partner Mico soon overtook its sales of diesel technology for stationary engines used in agriculture. In 1954, Bosch acquired an initial stake of a good 9 percent in Mico, which it then steadily increased over the years. Today, Bosch holds a roughly 70 percent stake.

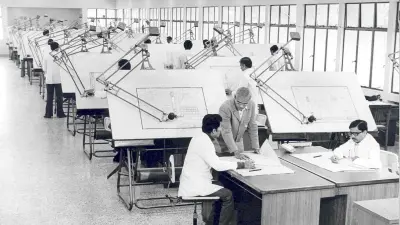

Since 2008, the company — with locations in Bengaluru, Nashik, Naganathapura, Sitapura, and Goa — has been called Bosch Limited. Its products now bear the Bosch name as well. For many years now, however, Bosch operations in India have gone far beyond solely manufacturing and marketing. Engineering work has come to special prominence. For the low-price vehicles made in India, for example, local specialists develop products such as robust engine control units that are easy and inexpensive to produce. To coordinate the company’s research and development activities in the region, Bosch set up its Research & Technology Center in Bengaluru in 2014, and this was followed by a branch of the Bosch Center for Artificial Intelligence (BCAI) in 2017. In 2019, Bosch opened the Robert Bosch Center for Data Science and Artificial Intelligence at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras, one of the country’s leading engineering institutes.

One of the things that sets Bosch in India apart today is the way its local IT activities have developed. Set up in 1998, Bosch India’s software center has seen a remarkable rise. Renamed Robert Bosch Engineering and Business Solutions (RBEI) in 2008, it now offers engineering services and IT solutions worldwide. Its activities extend beyond India, with its associates working for Bosch in six additional countries in Asia, the Americas, and Europe.

Author: Dietrich Kuhlgatz