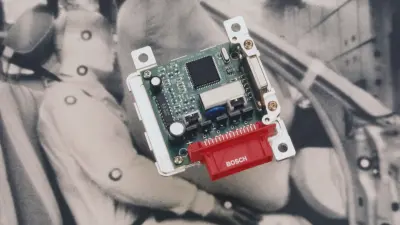

The common-rail system

One success story ends, while another begins

This is a success story that only appears not to have a happy ending. It is the story of 25 years of the common-rail system, the most widely used high-pressure diesel injection system produced by Bosch. Common rail marks the starting point of the diesel engine’s triumphant rise to popularity in Europe in the early 2000s. In view of Europe’s current CO₂ legislation, we now have to ask whether diesel has any future. But the next Bosch success story is just around the corner – in the shape of electromobility.

Even the developments that paved the way for our success story were anything but simple. It is the story of a visit that Robert Bosch paid to Rudolf Diesel toward the end of the 19th century. As it was proving difficult to get diesel fuel to self-ignite, Bosch was asked to try out his ignition device on a diesel engine. The outcome was dispiriting, producing excessive amounts of smoke but no power. Even lunch was an embarrassment, it appears. Robert Bosch had a mere three marks in his wallet, yet asking Diesel to lend him the money or pay his share of the bill was out of the question.

Many years later, in 1927, Bosch succeeded in making the diesel injection pump roadworthy when he installed it in a truck. Dieselpowered passenger cars were soon to follow, but for many years their clattering noise meant they sounded more like tractors. The common-rail-system was destined to change that. It made diesel engines more efficient and economical, and flexible pre-injection reduced the amount of noise they emitted. It was developed by the Italian engineering company Elasis, with Fiat and Mercedes acting as pilot customers. Yet one thing was clear to all of them: if one company could commercialize common rail, it was Bosch. So it was that Bosch took over where Elasis had left off, including its patents and its engineers.

A high-pressure environment — for the engineers too

Nonetheless, there was still a long way to go to production readiness, and it was here that Franz Fehrenbach and his team came in. Fehrenbach was head of the diesel business in 1997, when common rail first appeared on the market following a string of setbacks. Back then, it was not just the systems that were working under high pressure, but the engineers as well. Some of them would leave home every morning at four to drive from Feuerbach to the Bamberg plant, where the processes were still far from stable. For example, the nozzle needle play in the injectors had to be manufactured with micrometer accuracy, and the benefit reaped from the pilot series was at first not even half as great as expected. The engineers analyzed the prototypes overnight so that the test results would be available to the production team the next day.

Years later, after becoming CEO, Fehrenbach would cite this level of dedication as an example of Bosch’s staying power. However, as he was later to realize, these tribulations prior to market launch were just a foretaste of an even greater crisis that would emerge in 2005. The lubrication layer on the bushings of the common-rail-pumps became scuffed, steel rubbed against steel, and the bearings began to seize up. This “bushing crisis” forced Bosch to stop production, bringing manufacturing activity to a halt at its most important customers — the worst-case scenario for an automotive supplier. In this extremely tense situation, it took two to three weeks to find the cause. The fault was in the Teflon coating, which had been incorrectly produced by a sub-supplier. But until the fault had been rectified, the company remained under pressure from its customers – pressure that felt higher than 2,000 bar, as Fehrenbach would say years later.

Years of growth followed, many of them in which common rail was the crown jewel of Bosch’s business activities, being produced at 12 sites in ten countries. But then diesel fell into disrepute when automakers were found to have manipulated exhaust-emissions values. With software from Bosch embroiled in the controversy, the company launched an independent investigation in close cooperation with the authorities. At the same time, it introduced a code of ethics for its developers and engineers.

Technically as well, diesel engines have been rehabilitated. Reducing their emissions to such an extent that they no longer have a material negative impact on air quality was another engineering feat. Yet for some time now, the share of diesel among newly registered vehicles in Europe has been falling. By 2035, its share could plummet to nearly zero in light of the European climate action plan, which calls for all new cars to be zero-emission vehicles by then. That could mean the end of the diesel engine — unless, of course, it were to be run on climate-neutral synthetic fuels.

But it’s good to know that Bosch is already growing with electromobility. It’s not so much a case of the end of a success story start of a new chapter.

Author: Ludger Meyer