Industrial technology at Bosch

“Well-engineered, top-quality special tools”

For Robert Bosch, proper tools and modern machinery were essential from the very start. His early focus on improving and enhancing equipment and processes paid off. To this day, the company’s own plants, as well as many customers worldwide, use Bosch’s innovative industrial technology in their manufacturing operations.

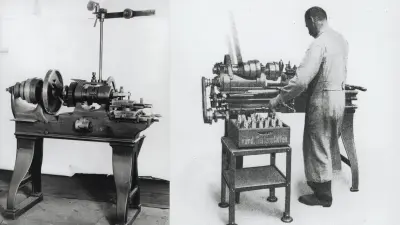

Robert Bosch was full of praise for the man he hired in 1902, calling him “extremely proficient.” But this wasn’t just a question of Otto Schaerer’s industriousness. Robert Bosch also valued his outstanding inventiveness. Schaerer held a patent for a lathe that the mechanics in magneto production used to turn the milling tools that were needed. Robert Bosch — who, in his own words, “never ceased to consider what other products [he] might manufacture as well” — made him the head of a newly created machine-tool department. The sustained sharp rise in demand for magneto ignition devices for automobiles had made such a department necessary.

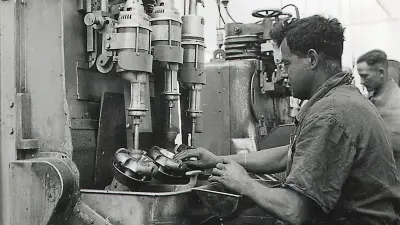

To be able to supply the required volumes, Bosch did all it could to adapt its machinery and equipment to the various types of ignition devices. And as the market had little to offer in the way of suitable equipment, the company’s master craftsmen had to design a lot of equipment themselves.

This new product area allowed Bosch to kill two birds with one stone: he could be sure his associates had access to high-quality tools that were tailored to their needs, and he could expand the company’s product portfolio by making tools for other manufacturers as well. Under Schaerer’s direction, the new product area got to work. It made special-purpose machine tools for the company’s own use, along with lathes, grinders, and arbor presses that were marketed to customers through a catalog.

However, the rapid, runaway success of the magneto ignition device soon demanded more and more of the company’s human resources — including the associates working in the machine tool department. Work in the department came to a near standstill, and Schaerer was at a loss for a solution. With a heavy heart, Bosch sold the machine tool department to Schaerer in 1906. Looking back, though, he said he “should have kept the business in-house.”

In reality, Bosch continued to do much of the business in-house, as the sale affected only the range of tools and machines for external customers.

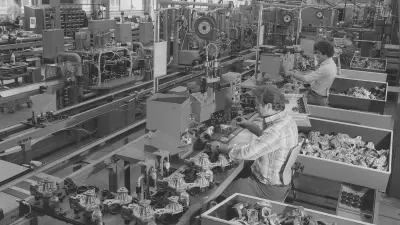

His associates continued making machinery for the company’s own manufacturing activities, and this machinery soon took on a significantly greater role. The senior master craftsman August Gößler summed up the situation in the associate newspaper Bosch-Zünder in 1925: “With mass production, extensive division of labor, and the often complex production of parts, a large-scale enterprise today needs a tool-making shop that is up to the task of making well-engineered, top-quality special tools.”

In the decades that followed, the “tool-making shop” would primarily serve the manufacturing operations for the company’s various products.

The Bosch manufacturing facilities were destroyed in the second world war. Once they had been repaired, the operating unit continued to develop positively. In the early 1960s, the restructuring of the company’s organization made industrial technology a discrete unit once more.

Over time, the focus shifted more and more to two segments of industrial equipment: electronic control technology and assembly technology. The leap in development from manually operated machines to electronically controlled machine tools was predigious. Where even the most minor changes in the manufacturing process had meant time-consuming adjustments to machines in the past, it was now possible to reprogram them in just seconds with the help of a code. Assembly technology also benefited from the new world of possibilities. Thanks to microelectronics, automation solutions that were initially only economically feasible in mass production could also be used for small and medium-sized production runs. Flexible automation was the new buzzword. Production engineers initially defined the individual assembly technology modules with manual workstations, double-belt assembly lines, and assembly machines. Subsequently, they designed flexible, customizable ways of combining manual and mechanical tasks that could be coordinated with machine cycles or work largely independently of them.

By acquiring Mannesmann Rexroth AG in 2001 and setting up Bosch Rexroth AG, Bosch strengthened its industrial technology operations and gained essential expertise in drive and control technology.

For Bosch Rexroth, the way forward lay mainly in the combination of control technology and products for highly automated manufacturing processes. With concepts such as “smart factories” and “Industry 4.0,” the focus shifted increasingly toward connecting people, machines, and processes. The underlying hypothesis — that people, machines, and products would constantly communicate with each other in the future and thus make manufacturing processes more efficient — soon proved correct.

Author: Bettina Simon