Robert Bosch’s journey to New York City in 1884

Setting off for the New World

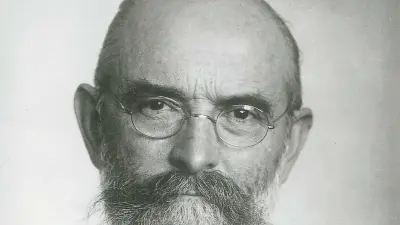

In 1884, the 22-year-old Robert Bosch embarked on a journey to New York City. He was keen to broaden his knowledge and experience by learning from the great pioneers of electrical engineering such as Thomas Alva Edison and Sigmund Bergmann. In many ways, it was a journey that would leave its mark on him.

The lights go on

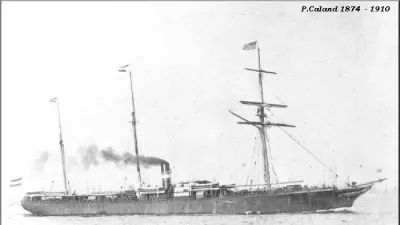

The room was glaringly bright. With the luminous intensity of 40,000 candles, some 2,500 light bulbs were shining. On entering the Munich Hoftheater in 1884, the young mechanical engineer Robert Bosch was undoubtedly dazzled, if not impressed. The radiance was made possible by a patent held by the U.S. inventor Thomas Alva Edison, which the German Edison Company was now using. At the time, Robert Bosch was spending a semester as a guest student at the Technical University in Stuttgart. The professor of electrical engineering there sent him to Munich to take a look at the electrification of the Hoftheater and to obtain a letter of recommendation for a New York-based company supplying products to Edison. The work Robert Bosch had done at German companies by this time meant he had learned a lot about engineering and organization. And as he had also completed his compulsory military service, he could give his dreams of seeing the world free rein. With the letter of recommendation and a share of his inheritance in his pocket, he set off for Rotterdam in 1884, boarding a ship bound for New York City on May 24.

Between hope and trepidation

A diary that he kept during the twelve-day crossing gives us a glimpse of his hopes and fears for his stay in the United States: “I’m curious to see what effect my recommendations will have, and whether I might not have to start at the bottom after all. It could potentially set me back years if I had to work as a waiter or a baker's boy.” There was no doubt that he wanted to achieve something: “But whatever, I now want to do all I can to get ahead, and it would be strange if I didn't make it in a country where many a person who didn’t even have the good will to do so has made something of themselves. And good will is something I won’t be lacking in.”

Welcome to New York City

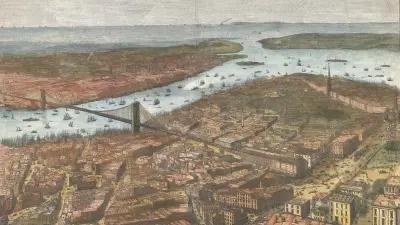

On disembarking in New York City, he was greeted by the same view as every other European immigrant at the time. He was thrilled: “Gradually, the entire shore comes into view. It is impossible to mention everything, you have to see it with your own eyes... A spa hotel like a palace, big enough for 6,000 people... The coast of the continent is mountainous, which is beautiful. — Brooklyn Bridge. — Seeing all the hustle and bustle fills me with joy. Come and see!”

New York City must have been overwhelming for the young man. He witnessed the busy harbor with its countless ships and, of course, the city’s new landmark, the Brooklyn Bridge, recently completed in 1883. Spanning 486 meters, it was then the world’s longest suspension bridge, linking New York City on the island of Manhattan with what was then the independent borough of Brooklyn.

A little bit of home in a foreign country

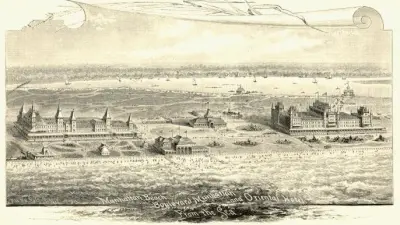

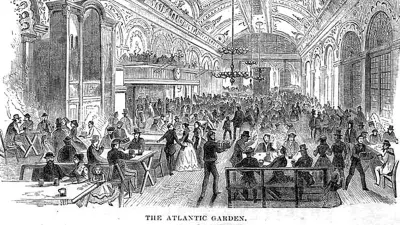

Like many other German immigrants, Robert Bosch is likely to have found somewhere to live in “Little Germany” on the Lower East Side. It was home to more than 250,000 people, and German was the language of everyday communication. Beer was served in many establishments known as “beer halls,” and there were also theaters and music venues. Initially, people continued to live mainly among their fellow countrymen and women, and worked side by side with them in the factories that provided employment. It seems that this situation was no different for Robert Bosch. After a visit to a pub and lively exchanges with the locals while he was working in London the following year, he wrote: “I think I’ll learn more English here in three months than I did in America in a year.”

Electrifying times

The Manhattan of the 1880s was densely built up, with a population of 1.2 million. The neighboring towns were connected by multiple railway lines, which transported workers to the factories. In 1878, the first elevated railway line was opened to help cope with the increasing traffic and relieve congestion on the streets.

Buildings were going up at every turn. However, New York City was at its most magnificent at night, when the city was illuminated by countless electric lights. In 1882, Thomas A. Edison had commissioned the construction of the first stationary power station, thus helping to make the electrification of New York City a reality.

Working for the pioneers

Robert Bosch was also enthralled by the new technology. Thanks to his letter of recommendation, he obtained a position at S. Bergmann & Company. Sigmund Bergmann was living the American dream: In 1870, at the age of 18, he had left Thuringia for New York City, where he worked his way up from unskilled laborer to successful entrepreneur. Together with Edison, he devised components for the new electric lighting, which he made in his factory — with Edison as a partner. Edison had been using the top floor of the building on New York’s Lower East Side as a test laboratory since 1882, and Bosch met him there several times.

However, Robert Bosch was let go when business at Bergmann’s began to falter. But he soon found a new job at the neighboring Edison Machine Works, which manufactured products similar to Bergmann’s. It was a confined space where around 800 mechanics, laborers, and clerical staff worked. Here as well, Robert Bosch found it hard to reconcile his sense of justice with the working conditions he saw. The common practice of hiring and firing, under which workers were quickly taken on and just as quickly let go depending on the economic situation, left workers and their families without any protection.

Organized labor

To improve workers’ lot, trade unions were also being formed in the United States. Robert Bosch joined one of these organizations, the Knights of Labor. Established in 1869, its demands included an eight-hour working day and the abolition of child labor. Boasting 100,000 members in 1884, it was by no means a small union. The Knights of Labor were very progressive for their time, accepting women and Black people as equal members. Asian workers, however, were excluded. Indeed, it may well have been the treatment of Asian immigrants and the still strict racial segregation in some parts of American society that colored Robert Bosch’s view of the United States. He wrote that he had gone to America partly because his father’s and elder brothers’ views had turned him into a young democrat. But his verdict of life there was less enthusiastic: “Being a dreamer, I did not like living in a country where the cornerstone of justice was missing: equality before the law.”

Returning home

In the end, the young Robert Bosch failed to really “make it” in the United States in the way he had envisioned on his way there. Whether this was due to the turbulent business world or to social and personal circumstances — he had become engaged and was sorely missing his fiancée Anna in Stuttgart — is a matter of speculation. He felt the urge to return to Europe. In April 1885, he wrote to a friend: “As soon as I can switch to something else, I will.” He planned to look for a job in Rotterdam to “find a position where I can acquire not only manual skills but also learn about things like costing. After all, manual skills on their own are not enough.” In 1886, after stints in London and Magdeburg, he had acquired enough expertise to set up his own “Workshop for Precision Mechanics and Electrical Engineering” in Stuttgart. Robert Bosch’s experiences during his time in New York City were to have an influence on him as a person and an entrepreneur for the rest of his life.

Authors: Bettina Simon / Christine Siegel