A century of the Bosch horn

A blast heard around the world.

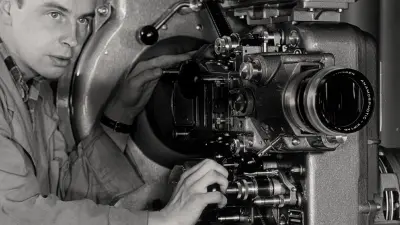

A loud rich sound attracted flocks of visitors to the Bosch booth. The Bosch horn was echoing through the huge exhibition hall.

Following a ten-year break, the first Berlin Automobile Exhibition after the war was held in 1921. In Europe’s largest exhibition hall, Bosch showcased its new ignition devices, lighting systems, oilers, headlights, and spark plugs. However, it was the new Bosch horn that magnetically drew visitors in with its distinctive sound. The visitors included the guest of honor Friedrich Ebert, the German president, who also could not resist pressing the switch on the horn to sound the signal.

A big noise on the streets

In the early days of motor vehicles, horns were anything but common. Cars themselves were still unusual enough for their appearance alone to draw attention to themselves, making any additional warnings unnecessary. But as vehicles grew more affordable, traffic grew steadily and safety regulations became stricter. In 1910, it ultimately became mandatory for motorists to use signals. Cities quickly filled with the din of throaty klaxons, piercing sirens, honking bugle horns, shrieking air horns, and squeaky bulb horns.

The cacophony was more than anyone could take, especially along major streets and at intersections. The noise bothered and frightened pedestrians and other road users. Another solution had to be found. In April 1914, Bosch registered a patent for an “electric signaling pipe,” but the outbreak of the first world war prevented any further development. Bosch was not able to start working on the horn again until early 1919. Bosch’s head of development, Gottlob Honold, gave his associates a new task: developing a signaling device that could be heard from a distance, and that was easy to use, consumed little energy, and could be produced in large numbers. The device needed to sound good without being expensive.

The ultimate solution

The result was a buzzer system. Although several such systems had existed in the past, none had proved suitable for the task at hand. The new system involved an electromagnet that caused a membrane to vibrate, generating a relatively pure sound — albeit without the required range. After experimenting for a while, the engineers discovered the right concept. Using the “closed pipe” principle from organ-building, they installed a second membrane that generated harmonic frequencies. In combination, the root and the overtone complemented and amplified each other, generating the pleasing, pure sound that would become typical of car horns. The result was a volume loud enough to be heard two kilometers away on an open road.

“Keep the noise down”

Horns were blaring on the streets at all times of the day and night. Drivers truely loved their Bosch horn, using it to signal before or during overtaking, and honking at oncoming drivers on narrow streets, while making turns at intersections, or just for the sake of it. Terrified pedestrians and sleep-deprived residents of local streets soon started to complain. A throttle valve for a second, quieter tone was soon mandated for urban traffic, which in Stuttgart in 1924 was subject to a speed limit of 30 kilometers an hour. However, the temptation to press the other button to trigger a louder sound proved irresistible. In a series of now famous advertising posters, Bosch stepped in and made a case for more considerateness: “Keep the noise down. Warn others with the Bosch horn.”

The company also developed a special Bosch horn for fire trucks. The distinctive two-tone sound was generated by alternately sounding a small and a large horn.

Use of the strident Bosch horn even extended beyond the world of automobiles. According to a report in the Bosch-Zünder in-house newspaper from 1927, it was also used in politics. Having wisely brought the Bosch horn with him to the meeting just in case, the vice chairman of the Frankfurt city council used it to restore order and quiet an agitated councilor. The account of the scene likely brought a smile to associates’ faces.

Competitiors advertises with “Bosch”

The new technology quickly found acceptance, and Bosch horn also gained popularity abroad. In fact, it became so popular that it was not only used in nearly all cars, but also inspired imitations in Germany and elsewhere. One particularly brazen manufacturer advertised their copycat version as a “full imitation of the Bosch horn.” Aware of the unrivaled quality of its products, Bosch remained calm, taking the view that this was, in the end, an endorsement of its own product. Just one year after regular production started in 1921, the 10,000th Bosch horn left the factory. The 100,000th followed in 1923. By 1929, the company had already sold more than one million horns.

Safety and comfort

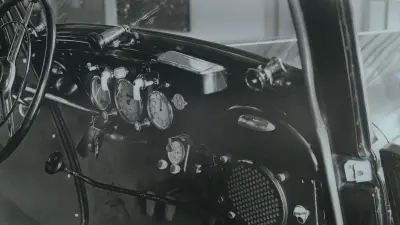

The launch of the electric horn allowed Bosch to continue evolving into a state-of-the-art automotive supplier while also revolutionizing the technology behind motor vehicle horns. Its loud, clear sound was a rousing success with motorists, making cars more suitable for everyday use, as well as making the roads safer. The Bosch horn owed part of its success to ease of use. Drivers only needed one hand to press a button and sound the horn.

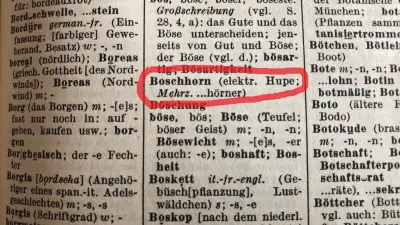

Further automotive technology breakthroughs, such as windshield wipers, servo brakes, and turn signals (“Bosch direction indicators”), followed over the course of the 1920s. For motorcycles, the company developed a separate motorcycle horn. Originally mounted on the body, the elegant Bosch horn was ultimately to disappear under the hood and take on a different appearance. However, the fact that its name later became common parlance and even made it into the German dictionary illustrates its tremendous impact.

Author: Angelika Merkle