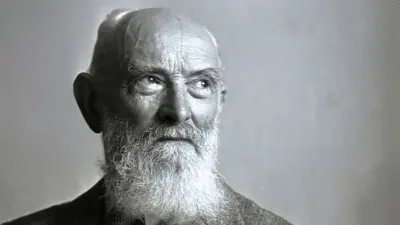

Robert Bosch — advocate for democracy

Political education, pacifism, and international understanding

On January 30, 1933, Robert Bosch’s political commitments lay in ruins. Bosch was forced to look on as the National Socialists came to power, only to establish a dictatorial, inhumane regime right in the heart of Europe in the years that followed. Robert Bosch was a forthright opponent of any radical movements, from both the left and the right. He was a democratic liberal and a champion of political education and freedom of the press, which he believed could open people’s eyes, bring people closer together, and foster a peaceful and democratic society. But Bosch’s efforts proved fruitless, during his lifetime at least.

Meetings in small circles

Robert Bosch’s democratic values were founded in his liberal upbringing. His father, a freemason, embodied fundamental ideals such as freedom, equality, brotherhood, tolerance, and humanity. As a young man, Robert Bosch soon took on his life motto: “Never forget your humanity, and respect human dignity in your dealings with others.” In his letters to his fiancée Anna Kayser from his travels in the United States in 1884/85, Bosch wrote about social issues and the political system. He wrote that she had a right to form her own opinion. At the time, it was by no means a given that a man would advocate for a woman to be on equal footing — for Bosch, this was an expression of his deeply held convictions.

As a young entrepreneur, Robert Bosch engaged in passionate and thought-provoking discussions with his neighbor, Marxist theorist Karl Kautsky, and communist Clara Zetkin. Throughout his life, Bosch maintained close links to the liberal German People’s Party (DVP) as well as the Social Democrats (SPD). Bosch always valued freedom of speech very highly, but only rarely disclosed his political opinions to the general public and never became a member of a political party.

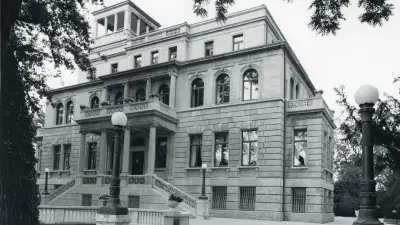

Nevertheless, he still found ways to express his political beliefs away from the challenges of his business. Shortly after the outbreak of the first world war, Bosch founded the 1914 German Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft von 1914) together with author and design engineer Karl Gustav Vollmoeller, poet Richard Dehmel, and industrialist and politician Walther Rathenau. Taking inspiration from the political clubs in the United Kingdom, the 1914 German Society was a place for people of any political conviction or social standing to discuss and debate their opinions with one another, as equals. Bosch purchased the Pringsheimsches Palais, a stately home in Berlin, and made the furnished property available at a nominal rent, motivated by a desire to give “fair interaction among political opponents a chance,” as the Bosch biographer Theodor Heuss wrote. In the final years of the Weimar Republic, as the debate and tone turned increasingly nationalistic and intolerant, Bosch took more of a watching brief.

Democratic diversity of opinion

Freedom of the press and a pluralistic society were important issues to Robert Bosch during his lifetime. Bosch firmly believed that all citizens should be free to form their own opinions on the basis of a diverse media, which is why he invested in newspaper, magazine, and book publishers. In 1912, Bosch purchased the weekly newspaper Die Lese, which was initially designed for people from non-academic backgrounds and helped support Bosch’s efforts to educate the general public. Bosch even supported the Schwäbische Tagwacht on multiple occasions starting in 1916, even though the social-democratic newspaper was often critical of Bosch and his company. Support for Bosch’s favored political parties, the DVP and SPD, came in the form of access to various publications. Bosch’s acquisition of Deutsche Verlagsanstalt and its subsidiary publication, the Neues Tagblatt newspaper, gave the DVP a party organ. At the same time, he was also financing the moderate Sozialistische Monatshefte magazine. Bosch’s efforts were aimed at helping people develop an understanding of democratic rights and obligations at a time of political stability in the Weimar Republic.

Robert Bosch was also dedicated to funding political education. Beginning in 1920, Bosch co-financed the newly founded German Academy for Politics, which aimed to give students from as many different backgrounds as possible access to sound historical, political, and democratic education, independently of the German state and political parties. In 1933, the National Socialists forced the academy into line, dismissing Jewish professors and those deemed to be politically unreliable — unless they had already emigrated, that is. The propaganda ministry took control of the academy’s curriculum and administration, bringing an end to its independent and democratic teaching.

The only way is through understanding

Following his experiences in the first world war, Robert Bosch was a pacifist through and through and became a driving force of international understanding, particularly between Germany and France. He joined the German section of the Committee for Franco-German Relations and invited German and French war veterans to Stuttgart as “pioneers of peace” in 1935.

Bosch’s commitment to a pan-European confederation of states followed the same aim, of preventing Europe from going to war again. He was a member of the executive committee of philosopher and politician Richard Coudenhove-Kalergie’s Pan-European movement. Both men firmly believed that militant nationalism was an obstacle to justice and social equality. But the outbreak of the second world war meant that the movement had failed in its primary objective.

Hopes are dashed

The rise of the National Socialists in Germany destroyed many of Robert Bosch’s efforts. The Weimar Republic crumbled, and large swathes of the German population were taken in by the National Socialists’ promises. On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor. The dictatorship lasted for 12 long years and culminated in the catastrophic second world war and the Holocaust. Robert Bosch, who always rejected the National Socialist ideology, was caught in a dilemma: if Bosch wanted to retain his life’s work, the company, he would have to demonstrate a minimum amount of cooperation. The company was classified as being “crucial to armaments production” and employed forced laborers. But even in such difficult times, Robert Bosch still found ways to do the right thing. He supported the members of the July 20 resistance group and provided financial help and other assistance to Jewish citizens attempting to flee Germany. Robert Bosch remained a keen advocate of democratic principles right up to his death in 1942.

He enshrined his values in his will, laying down guidelines for managing the company’s assets: “Apart from the alleviation of all kinds of hardship, support should be given to promote health, education, programs to help the gifted, international reconciliation.” Bosch’s charitable commitment is continued today by Robert Bosch Stiftung GmbH, the owner of the company. True to the values of the company founder, the Stiftung supports projects that address the question of how democracy can be strengthened in Germany and Europe.