Striking a balance

The secret to a successful transition in Bosch history

Our world is in flux. Change is a constant at companies as well — and Bosch is no exception. Change means both opportunities and challenges. More importantly, it demands flexibility from a company and its workforce. However, the present Bosch workforce is not the first to face major upheavals. And whether today or a century ago, the key to success is innovativeness and flexibility.

There have been many varied examples of disruption in the company’s history, as we can see if we go back 100 years to the time after the first world war. The old world was no more, and the economy was in the throes of restructuring — both in terms of production methods and in terms of labor relations. Bosch had to face the fact that it could not just pick up where it had left off in 1914. Instead, new conditions also called for new departures.

Until 1914, most cars worldwide had been equipped with Bosch magneto ignition systems. But the war changed everything. Sales on international markets were no longer possible and strong rivals had come to the fore outside Germany. Bosch found itself faced with dwindling sales and budding competitors that were soon able to provide products of equal quality at a lower price.

Back to the top

Bosch focused on tried-and-true strategies that had already proved successful and that have paid off ever since: innovation, quality, internationality, and product diversity.

Products such as lighting systems, starters, and generators — all of which had been added to the portfolio before the war — were evidence that Bosch could do more than just make magneto ignition devices. Thanks to its many innovative associates, Bosch had become a specialist in the field of automotive technology. This expertise benefited Bosch when it came to new products, such as windshield wipers and electric horns.

The associate’s self-image

What made life difficult for associates at the time were the new demands placed on work and products, and thus also on their self-image. To stand the test of global competition, the company and its production activities needed to become more agile. In Bosch’s first decades, products had been made individually, with time and care, resulting in outstanding quality. By the 1920s, however, that approach was no longer efficient enough to face the competition. Quality was still of the essence, but manufacturing had to become faster and more streamlined, and with a greater division of labor. For highly trained skilled workers, this new approach meant a change, as they no longer needed to make use of all their skills. The assembly line became a symbol of transformation, and associates found themselves asking if the products being made had the potential to be as good as before. Some at Bosch found themselves living through both tough economic times as well as an identity crisis. A long-standing corporate culture with values that Robert Bosch himself embodied — such as trust in associates and the encouragement of initiative and cooperation — helped them put this crisis behind them. Even back then, associates could be kept informed and encouraged to follow the path of change through the exchange of information in the newly founded associate paper ’Bosch-Zünder“ and, conversely, they were able to address their concerns and worries — an interplay that takes place today via the Bosch Zünder Online and its comment function.

A path into the future

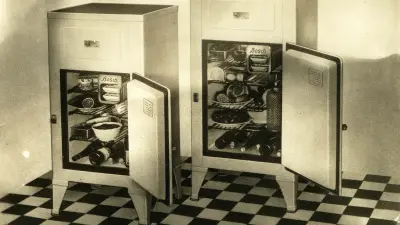

In the mid-1920s, it became apparent that, despite the advantages of flexibility and change, they are not sufficient when a company is entirely dependent on a sector of the economy that has been plunged into turmoil. That is as true today as it was 100 years ago. When automotive production collapsed in 1925, the company saw the need to reduce its dependency on automobiles and ’add more strings to [its] bow,“ as Robert Bosch put it. The solution? To explore new product areas where the company could leverage its rich expertise — ones with a bright future. Commencing production of refrigerators, power tools, hot-water appliances for bathrooms and kitchens, and car radios was made easier by Bosch’s combining its abilities with those of other companies, such as Blaupunkt and Junkers. Today, Bosch is investing in the internet of things and artificial intelligence. One hundred years ago, however, television technology was a market of the future that the company successfully set its sights on.

Open to change

Sales miracle instead of mood killer

It may not always be necessary to welcome every new development with open arms, but it is important to keep an open mind. After all, it may just pay off in the end. Robert Bosch, for example, initially dismissed radios when they first appeared in the market. At a get-together with acquaintances, he saw how the guests gathered around the device, stifling conversation. Annoyed, he left the party. Despite this, his company entered the promising new radio market only a short time later. Radios would continue to be a successful line of business for Bosch for decades to come.

From the 1930s to the 2030s

By the start of the 1930s, Bosch had fundamentally changed its portfolio. The company had made its manufacturing activities more profitable and had evolved from a mere supplier of automobile parts to a diversified electrical engineering group with pioneering technological solutions.

While other companies were hit hard by the Great Depression, the decline in Bosch’s business fortunes was comparatively modest, thanks to a combination of farsighted management, flexible and dedicated associates, a commitment to innovation, and global presence, all held together by a distinctive corporate culture. Even if the framework conditions may be different today, these evolved success factors can accompany successful change that will take Bosch successfully into the 2030s.

Author: Christine Siegel